Nancy Jennings was an ‘unfortunate’, a left over euphemistic Victorian word for a prostitute. A native of Birmingham, Annie, as Jennings preferred to be known, had found herself living in the Irish quarter of Leicester by the beginning of January of 1912, in a small two room cottage at No1 Court C, just off Archdeacon Road. She was described as stout and cheerful woman who kept a strict routine, and her next birthday was to be her 50th. Sadly, she wouldn’t see it.

On the morning of the 2nd January 1912, the barmaid of The Crown & Cushion Public House located on Belgrave Gate, Elizabeth Halford, and customer Edward Gamble, had been joined in the pub by 28-year-old rubber hand named Archie Johnson. Johnson, according to Halford, had arrived at around 11.30 am. She recognised him instantly as he also drank at her husbands pub, the nearby Woodboy Inn, in Woodboy Street, just yards from the Police Station located there. No sooner had she pulled him a pint than a Soldier in the York & Lancashire Regiment, William Stanyard, also walked in an ordered a beer. Upon receiving his drink, the Private sat a little away from Johnson, however the pair soon struck up a conversation based, as Halford recollected, around Johnson’s exclamation that he had also been in the army. Their chat lasted around 15 minutes, with the Private explaining he had stopped off in Leicester en route to Coalville, whilst Johnson proudly boasted that he was still on the reserve list and had, by matter of fact, been summonsed to appear at Yarmouth the next day by the Army.

At sometime near to 11.50 am, Annie Jennings entered the pub and, upon receipt of her drink, stood at the bar before moving to a window seat. Initially the two parties did not engage with one and other. However Halford noted, some thirty minutes later, that Stanyard, Johnson and Jennings were in conversation At 12.30pm Jennings left the pub, swiftly followed by the Private. And so Johnson turned his attention to Edward Gamble. Gamble, an elderly lodging house nightwatchman, had been in the pub since 10:55 am, observing and loosely taking part in the talk from then on in. Johnson conversed with Gamble for some ten minutes after Jennings and Stanyard’s departure, giving Gamble his white muffler (scarf) to protect the older man against the winters chill, and ordering him a pint of beer before he left himself. Whilst in the process of leaving the pub, Johnson arranged to meet with Gamble at 2.30 pm for a continuation of their drinking session. Johnson never turned up.

Private Stanyard and Jennings were spotted together in Belgrave Road at approximately 12.40 pm. And the couple were seen entering Court C some minutes later. At 1.30 pm, Private Stanyard was seen leaving Jennings’s small cottage, and Jennings herself, some minutes after that, was spotted with another young man. At 2.45 pm Jennings was then seen by 80-year-old Lily Bannister, in the Court Yard, carrying a bottle. Bannister was observant. She had also noted that just a short time prior to that Jennings sighting, she had seen her take a delivery of coal at her No1 address. The busy Bannister also claimed that at some stage during that afternoon Jennings had given her some rent money, and her rent book, and asked if Bannister would pay the rent on her behalf. This exchange took place inside No1, and whilst Jennings was locating her rent book, Bannister noticed a young man in the house. The young man called to Jennings to give Bannister a drink for her trouble, which Jennings obliged by pouring Lily a tot of rum. The last sighting of 49-year-old Jennings that day was at around 8 pm, when she turned up alone at the Earl of Cardigan Public House, in nearby Foundry Square. There she purchased a jug of beer and a glass of whisky (for the landlady) before departing with the jug. The next sighting was the following morning, and it was in the most disturbing of circumstances.

James McGregor was the caretaker for Court C. He knew every tenant there, and their habits. So when Annie Jennings, an early riser, had not been seen by 9.30 am, he sent his wife to a neighbour to see if she had seen her. The neighbour, Mrs Daniels, exclaimed she had not, and so the pair then made enquiries at Lily Bannister’s home. Bannister confirmed she had not seen Jennings either, and nor had another neighbour, Mrs Pallett. The posse of women, sans Daniels, then approached No1 Court C and entered the premises. The door was unlocked, and as they cautiously climbed the stairs they made out the shape of a body at the top. The women immediately returned to Caretaker McGregor in great distress, who then went to look for himself. McGregor returned to confirm their fears. At the top of the stairs laid Annie Jennings, naked save for her stockings and boots, with her throat cut, dead.

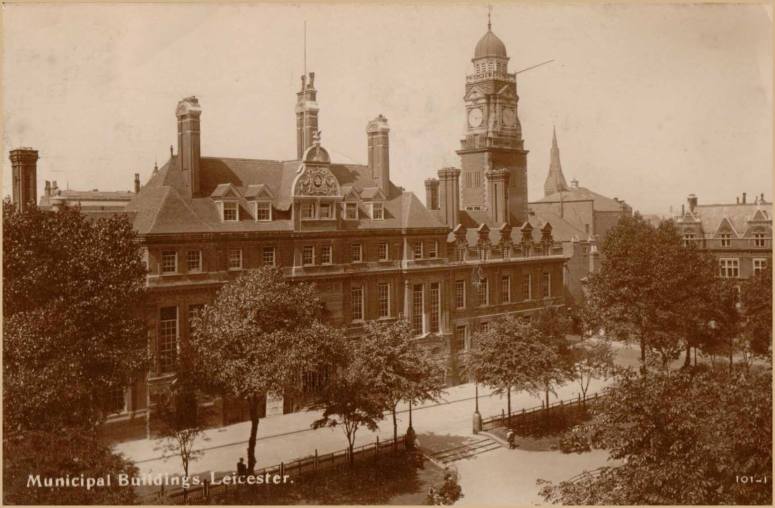

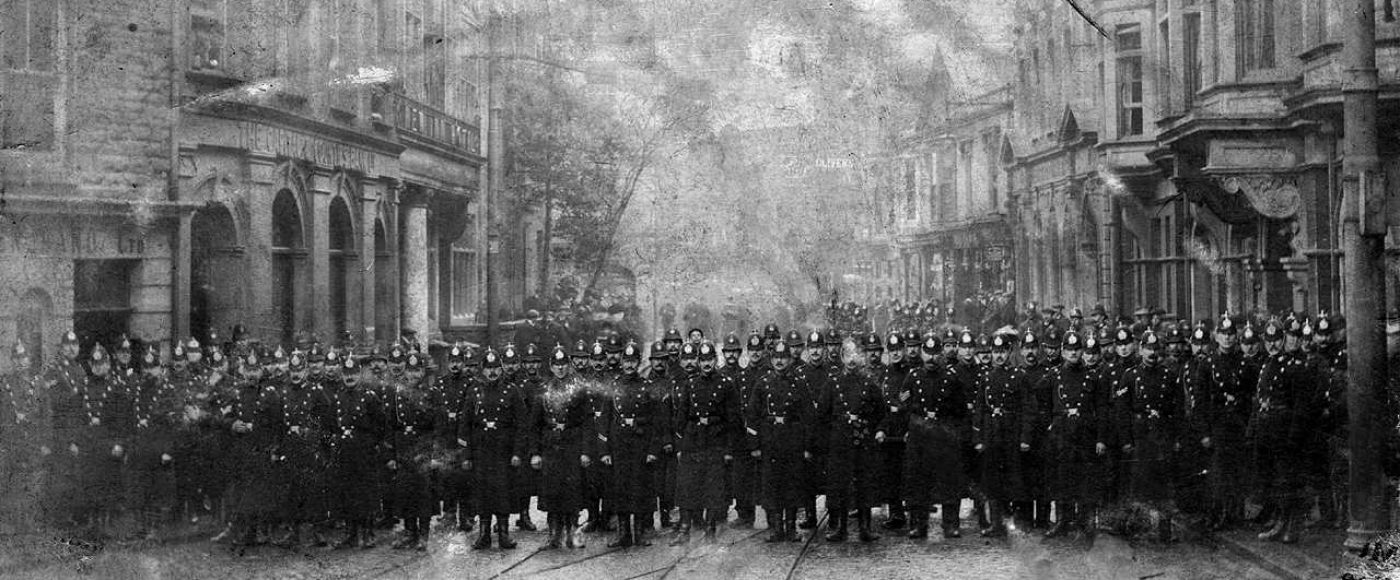

Detective Sergeant Kendall received message of a possible murder whilst stationed at Leicester Central Police Station, Town Hall in Municipal Square. Upon arrival he noted the scene. The empty rum bottle on the kitchen table, sitting along side a mineral water bottle, a glass and a teacup. Upstairs, in the bedroom, he spotted bloodstains on the bed and the mattress, whilst underneath the bed, he found a blood soaked blouse amongst other clothing, and an enamel basin, which also contained a large quantity of blood. Upon the carpet he found a bent and blood stained knife, apparently thrown. And the body of Jennings, on her back, head toward the bed, also covered in blood. A blanket had been placed under her head and shoulders, whilst a sheet passed across her back and under her arms. Despite being covered in blood, DS Kendall felt the knife found there had not been the murder weapon. He felt the murder had taken place on the bed, with Jennings either stumbling on to the floor, or the killer dragging her there. He noted the lack of lighting in the court, and the position of No1 meant no one could be seen entering or leaving Jennings’s home. Kendall was soon joined by Superintendent Herbert Allen and other constables. Dr Kirkland Chapel arrived at 10 am, and he merely confirmed what all present knew, pronouncing life extinct and requesting that the body be taken to the Town Hall Mortuary for Post Mortem by himself, and his partner Dr Arthur Barlow.

The Post Mortem revealed that Jennings had died due to the 4 inch cut to the left hand side of her throat. Time of death was estimated some 8 to 15 hours before the body had been discovered (not long and any time after she was last seen alive in The Earl of Cardigan Pub). Drs Chapel and Barlow disagreed on the murder weapon. Barlow sided with DS Kendall and dismissed the knife found at the scene, whilst Chapel felt it was the weapon which inflicted the wounds. Both Doctors agreed that Jennings had been subjected to an horrific beating. Curiously, Sergeant King, who was prepping the body, found two half crown pieces inside the stocking upon her left leg. However, even curiouser was the bite mark found upon the neck of the deceased.

Meanwhile, Leicester Borough Police were making enquiries in and around Archdeacon Lane, and these threw up two chief suspects, Private William Stanyard and Archie Johnson. Stanyard admitted to being with Jennings briefly during the afternoon at No1 Court C, however he claimed he left Leicester for Coalville during the late afternoon of the January 2nd, hours before Jennings was last seen alive, and witnesses confirmed this. He was swiftly dismissed as a suspect. Attentions now turned to Johnson. At 10.10 pm on January 3rd, Inspector North accompanied Detective Inspector Smith and Detective Constable Clowes to 38 Gray Street, in the Oxford Street area of Leicester.

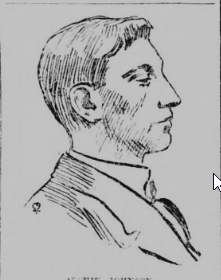

Here Johnson lived with his parents, and it was Johnson’s father who greeted this delegation of policemen. Johnson himself was upstairs and after a brief question and answer session, during which Johnson admitted being in the company of the deceased during the hours leading up to her death, claiming he had left her at around 4.15 pm. He was escorted to Leicester Central Station for an identification parade. Johnson’s clothing was stripped from him, and sent to Scotland Yard for analysis, and his boots where sent to a Doctor Willcox at St Marys Hospital in Paddington, London. Two witnessed picked Johnson out of the line up, including Mrs Bannister who noted Johnson as the man she had seen in Jennings home when she agreed to pay rent on behalf of the deceased. Other witnesses claimed to have spotted Johnson in the area of Archdeacon Lane after 4.15 pm and on that basis, the police decided to charge Archie Johnson for murder.

Despite the discrepancies laid open by witnesses in Johnson’s story, witness testimony can be notoriously unreliable at times, especially under the cross examination of an expert barrister. However, the prosecution in this case felt they held a strong piece of evidence in the form of a piece of blotting paper. As stated, the post mortem threw up a potential clue, a bite mark upon the deceased’s neck. A piece of skin upon which his bite mark had been made, had been removed by Dr Chapel from the dead woman and was, during the hearing, now sitting in a sealed glass jar next to the Doctor as he gave testimony. The skin was then pinned to a board. Next to this, also pinned to the board, was a piece of blotting paper, upon which the Leicester Borough Police had obtained the impression of Archie Johnsons own bite mark. A long and laborious exchange then followed, where the medicos debated on if the marks corresponded. However, it was really down to the jury to decide on if the two matched.

The verdict was returned quite swiftly. The jury found Archie Johnson ‘not guilty’.

The death is heart breaking, and murder can be particularly tragic and traumatic. And murder also runs the gamut of emotions not just for the victims family and community, but also those who investigate such crimes. The determination to capture the culprit is consuming, whilst focus on the job in hand, professionalism if you will, can be both physically and mentally draining. Yet both can be driving.

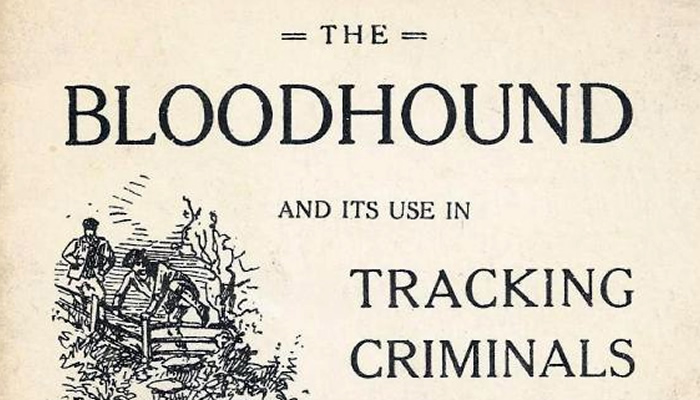

To achieve those duel goals of capture and conviction the police, over the centuries, have turned to science more and more. We can see the influence of the great police pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury in this Jennings case above. Spilsbury, less than two years prior to the Jennings murder, removed a patch of Cora Crippen’s skin to prove her identity, and likewise, Dr Chapel removed a piece of Annie Jennings skin in an attempt to identify her killer. The attempt failed, however the attempt in itself just proves just how influential forensics was becoming during that Edwardian and the early part of the new Georgian era.

As we can see, Leicestershire Police has always been willing to embrace science and all she has to offer, with their innovative work during the Narborough Murders, which massively influenced detective work globally, probably being the most well known.

However, we must not forget the pioneers. Those who sought killers with blotting paper.

For a more in depth review of this case, I recommend Leicester Murders by Ben Beazley.

Well, here it is, a blog site dedicated to the police and their history. It’ll never take off they said, and they may be correct. I don’t care; this is a passion, a need to share and an even stronger need to learn.

Well, here it is, a blog site dedicated to the police and their history. It’ll never take off they said, and they may be correct. I don’t care; this is a passion, a need to share and an even stronger need to learn.